Soren Kierkegaard Series (Part Two)

Many that hold to the modernist worldview often cringe (I’m being very gracious here) at the idea that truth can be subjective. Many conversations over the years have taught me there are three main reasons for this: first, most have no idea what subjectivity really means (though they think they do). Second, the denial of subjectivity has become axiomatic within the Christian sub-culture. Third, we have an addiction to certainty. This article will primarily focus on the first reason.

As I stated in the introduction article last month, many, if not most people, do not have a proper understanding of Kierkegaard (SK). One of the most misunderstood of his views is the issue of subjectivity. Although his perspective on subjectivity can be seen sprinkled throughout all of his writings, he spends the majority of his effort addressing the topic in his pseudonymous work “Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments”. However, In order to appreciate SK’s view we have to be aware of some brief context.

Hegelianism (The Philosophical Situation)

Kierkegaard had the unique challenge of arguing against Hegelianism and Christianity without completely disenfranchising philosophy or the State Church. This was no easy task since his audience was heavily influenced by both. His thinking was so unique and provocative for his time that it might be akin to someone today arguing against the validity of the scientific worldview while at the same time providing a completely unique alternative. What’s more, SK did this twice – once in the area of philosophy and once in the area of religion.

I have created a brief comparison chart of SK and Hegel here to help supplement this section.

Georg Hegel was a part of the philosophical school known as German Idealism. The impact he has had upon modern thought is incalculable. He created an audacious philosophical system that promised to render absolute truth. His objective system was so impressive that even the Church adopted its methodological practices. What’s more, both modern theology as well as modern science are products of his philosophical legacy.

Hegel’s boldest claim was that the mind has the ability to apprehend absolute knowledge. Hegel believed that it was the individual’s subjectivity that interfered with the mind’s ability to attain this knowledge. Therefore, Hegel created an objective system that accomplished this called dialectic. This methodology was not new, but was an adaption of Plato’s use of it in the Dialogues. The dialectic system can be illustrated using a simple equation:

Thesis + Antithesis = Synthesis

It was Hegel’s belief that every idea has some corresponding opposite to which it must be held accountable to. Through continually submitting an idea to this process one inevitably synthesizes the idea when the underlying dynamics have been reached (think analytics).

Christendom (The Religious Situation)

As you can imagine, the promise of absolute knowledge was much too tempting for the Church to resist. As it was, the Protestant Church had struggled to find its theological voice since breaking with the Catholic Church. It quickly seized the opportunity to reunite Scripture with absolutism in order to obtain “(T)ruth”. The audacious assumption of the Church was that simply applying a philosophical system to theology could result in the promised truth of Hegelianism. Ultimately, this resulted in the use of various objective methodologies, which is what was used to create modern systematic theology.

As was common throughout Europe, the Church was a function of the State. This lead SK to jokingly conclude that everyone within Denmark were Christians. This is where he derives the idea of Christendom (a nation of Christians). Since pastors were paid very well by the State, it led to a significant influx of individuals trying to get into the “ministry”. The problem of the State Church in conjunction with its new theological persuasion led to a completely stagnant church. For where does one receive a passion for the lost when everyone has been found? How is anyone motivated to be Christian when they have traded the uncertainty of mystery for the certainty of truth? Now that we have figured out the mystery of Scripture, what is left for us?

The important question that all of this begs is: Does the type of truth that objectivity claims to render actually exist in the real world, or is it only an ideal to make one feel certain about something that does not actually exist?

Kierkegaard’s Argument

SK had two problems with the objective approach. 1. The overall logic of its argument and the subsequent claim that this line of logic produces. 2. The use of objectivity as a theological method for determining truth.

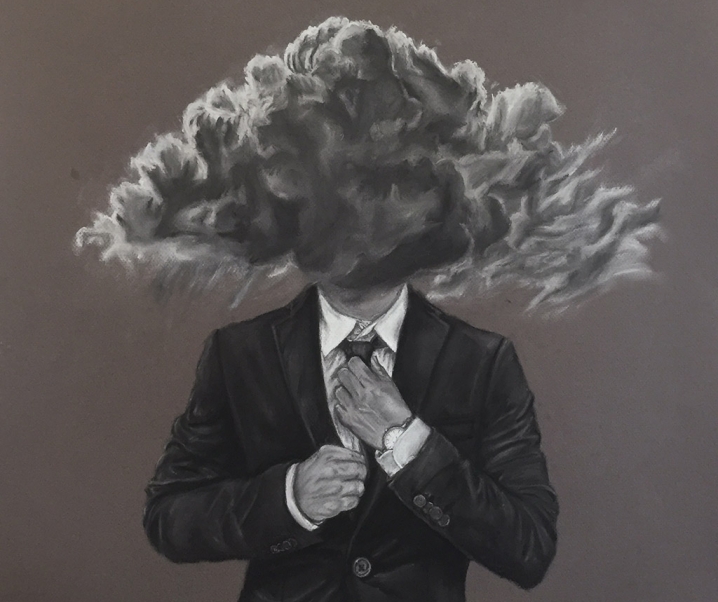

SK struggled to understand how an individual subject can claim that an objective methodology exists apart from the presuppositions of the individual, when it is the individual that has created the methodology. All of the assumptions that come with objectivity lack the objectivity necessary for the assumptions themselves to be deemed “objective”. In other words, it collapses under the weight of its own standard.

Add this pseudo-objectivity to the enterprise of theology and you have a perfect formula for producing illusions of truth. And, as I have stated elsewhere, not only was this exactly the situation the religious leaders of Jesus’ day found themselves in, but it is also the situation the modern church finds itself in. It is the illusion of truth that blinds us to the truth of Christ who stands before us.

In order to demonstrate the importance of SK’s point he takes the Socratic route (a bit of irony meant to counter Hegel’s Platonic sympathies). That is, Socrates demonstrated that truth is much more than propositional content, but must incorporate existence. SK argues that there needs to exist a differentiation between “the truth of Christianity” and the “individual’s relationship to Christianity”. Should the question of truth and its relationship to Christianity be posed ontologically or existentially?

Is Christianity something to be “known/understood” or is it to be “lived”? Here we see unique similarities between the life of Socrates and the life of Jesus. The question we are required to ask of Socrates is the same one we must ask of Jesus. Was the truth of Christ contained in his “words” or in his “actions”?

Or, is there yet a third alternative? Perhaps the message of Christ (it’s content) was captured through his action. In other words, the content of the divine Word cannot be separated from how that Word lived in the world. Therefore, the requirement for the Christian is to be a “living example of Christ” who preaches a gospel message of “action” instead of throwing out into the world the hollow promises of words. The promises of the cross would be meaningless if there were no actions to make that promise true.

The Truth of Subjectivity

I believe that despite what many modern Christians claim their faith is much more subjective than they think. Whether it is through the act of prayer, denominationalism, or how they live their faith, almost every aspect of our faith is a practice in subjectivity.

It is not belief in the absolute that causes a problem. In fact, I would argue that if you believe in the Judeo-Christian God, you must believe in absolute truth. But it does not follow that because God is absolute in His nature that the content of Christianity is as well. Especially when Christianity is theologically formulated through the subjective mind of the individual.

The problem occurs when we become arrogant in believing that we have the ability to understand truth on the same level that God does.

The problem occurs when we deny the truth of our subjectivity for the empty promises that objectivity brings.

Objectivity confines God to a box that He did not create. It limits God to simple-minded systems and concepts that He destroys. Jesus did not come to get rid of the Law – there was in fact nothing wrong with the Law. He came to destroy the system around it. He did not come to bring insurance, but assurance. He did not come to bring certainty, but gave us the privilege of experiencing his mystery.

When we understand that God uses human subjectivity to do His work we are more aware of His presence. When we are more aware of his presence we are able to do his will. When we are able to do his will, then we are being Christ to others.

So much more could and should be said regarding this, but for now I want to end with a beautiful quote from a young 21 year old SK that nicely summarizes the passion of subjectivity. While vacationing in Gilleleje Denmark SK reflected on the purpose of his life and recorded this entry in his journal.

************

What I really need, is to be clear about what I am to do, not about what I must know…It is a question of finding a truth that is truth for me, of finding the idea for which I am willing to live and die. And what would it profit me if I discovered a so-called objective truth; if I worked my way through the systems of the philosophers and was able to parade them forth on demand; if I was able to demonstrate the inconsistencies within each individual circle….What would it profit me if the truth stood before me, cold and naked, not caring whether I acknowledged it or not, calling forth an anguished shudder rather than confident submission? I will certainly not deny that I still believe in the validity of an imperative of knowledge, but it nonetheless must become a living part of me, and this is what I now understand to be the heart of the matter. It is for this my soul thirsts, as the deserts of Africa thirst for water.

zoritoler imol

December 2, 2023Simply wanna state that this is invaluable, Thanks for taking your time to write this.

Delfina Motamedi

December 3, 2023You made certain good points there. I did a search on the theme and found a good number of people will go along with with your blog.